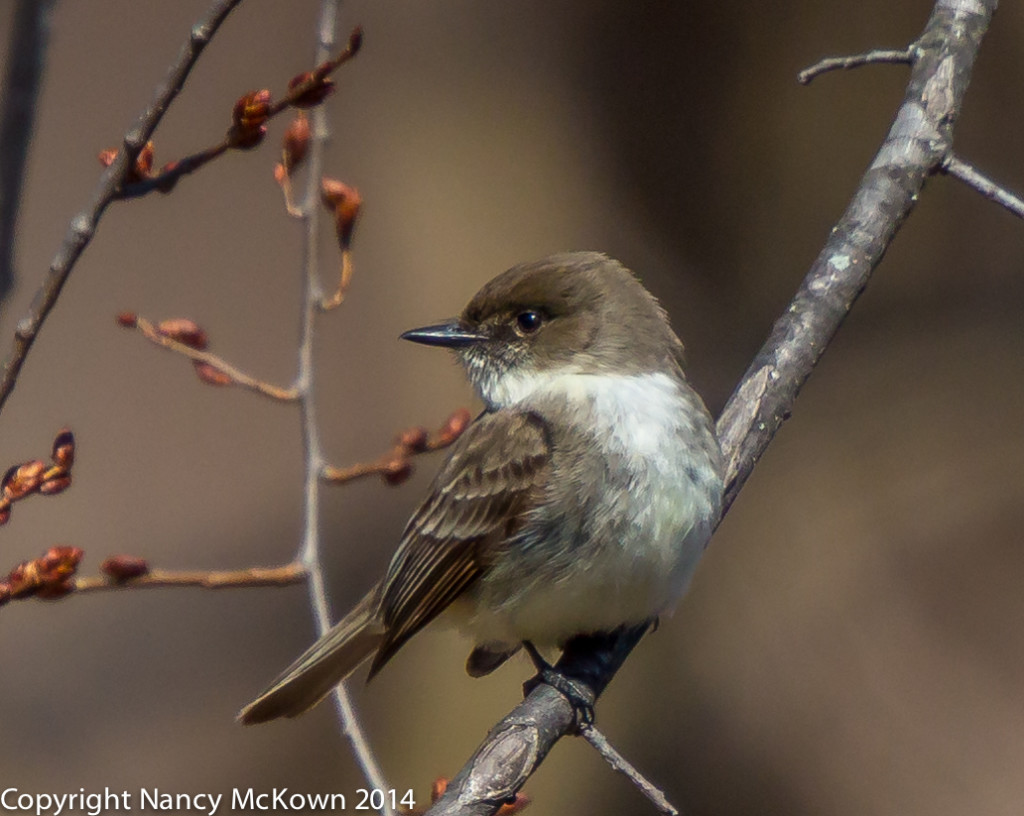

Photographing Eastern Phoebes at the Local Park

Eastern Phoebes are flycatchers found most often in semi-woody areas. They build cup shaped muddy, grassy nests in protected areas (like my porch). Despite the mess they make, I think they are beautiful song birds and love having them around.

Phoebes do not visit the feeder, but are still rather easy to photograph because they often return to the same perch after diving down to the ground for insects. The subtle brown, gray, yellow and white coloring of their plumage is lovely.

One interesting note: The eastern phoebe is one of the many bird species often successfully parasitized by brown-headed cow birds. Cowbirds, known as brood parasites, do not raise their own young. Instead of chick rearing, they use their time to continually produce eggs, which they then lay in other birds’ nests. For more information about how this survival strategy works for the brown headed cowbirds, and the toll it takes on the survival of eastern phoebes and other species, see this link.

ISO 640; f/8.0; 1/2000 Second

Tripod Support

I let my tripod do the heavy lifting when I photographed these eastern phoebes. The Manfrotto tripod I use is sturdy and provides steady support for my camera and long lenses. It’s collapsable, with three one-step fasteners on each leg for fast assembly and teardown. The center post (upon which the tripod head rests) also moves up and down, giving extra height when needed. With my gimble tripod head attached, maneuvering the camera and lens is a breeze. For more information about using the gimble head, see this post.

My only complaint about my tripod is its inability to get my camera situated close to the ground. The leg segments are a bit too long and do not spread out enough to lie flat. The center post can be removed, but the tripod still does not get down close enough to the ground. If I need to photograph from a low viewpoint, I find something, like my beanbag or other support on which to rest the camera.

Children Learning About Birds

I noticed a group of school children at the small park where I was photographing the eastern phoebes. They were exploring the pond, chasing the geese on the edge of the water, and following their teacher’s instructions to look to the sky, find a bird, and track its movements. The kids were doing their best to photograph the birds they saw, sharing 3 or 4 point and shoot digital cameras. The teacher had a tablet and was helping the children ID the birds they saw. Looked like great fun. Eventually, the students noticed my camera, tripod and me (in that order) and were delighted to learn that I was also watching and photographing unfamiliar birds.

ISO 1000; f/8.0; 1/2000 Second

Birding Web Resources for Children

There was definitely less bird activity at the park after the kids showed up, but I still had a productive day and I enjoyed watching the kids explore. I had a chance to talk with the teacher about what she was trying to accomplish on this outing. She referred me to several web resources that help children to learn about birds. Of course, there’s nothing better than getting the kids out to observe first hand and think about the wonders around them.

Two birding web resources for children that that I think are worthwhile are:

#1) Citizen Science

#2) BioKids